The article talks about the role and possibility of influence of integrated land use on transportation planning and vice-versa. It explores how appropriate interdependency and correct correlations between the two aspects of urbanization can be useful building blocks of attaining suitability.

It starts with understanding the variables of the built environment and their effects on travelling and mode choices. Various mathematical models have been devised with certain drawbacks. The paper talks about how they can be made more effective in predicting the travel aspects used in transportation planning. Applications of the theories shall be looked upon in the field of planning with suitable examples from India and abroad.

The problem of parking as an economic commodity or as a right will be analysed by studying case studies abroad and the situation is different in India, both in terms of mentality and at the policy level. The state of policymaking on green mobility will also be analysed by studying some important relevant policies of India.

Finally, various relevant concepts related to Integrated Land Use and Transportation Planning (ILUTP) would be seen analysed using network analysis and centrality study and how various SGDs get positively affected by their virtue of it.

Importance of Integrated Land use and Transportation Planning

Urban India with a population of 377 million accounts for around 35% of its total population, living in 8000 towns or cities. This has direct implications for the increase in private vehicle ownership. Thus, rapid motorization appears to be a major urban concern. The air quality index in major cities like Mumbai, Delhi, and Bangalore is low, owing to the pollution caused by vehicles. On average, 40% of the pollution is caused by vehicles.

It is from this tangent of urbanisation and sustainability that ILUTP becomes one of the most important aspects to be considered while planning and policymaking from any urban space.

For the purpose of studying ILUTP, papers related to built environment variables and how they affect travelling and mode choices, written by pioneers in the field like Robert Cervero, Prof. at the University of California, Berkley, were studied.

Built Environment and Travelling

There are various aspects that work together to finally determine how travelling of people work in a city.

The ‘3Ds’

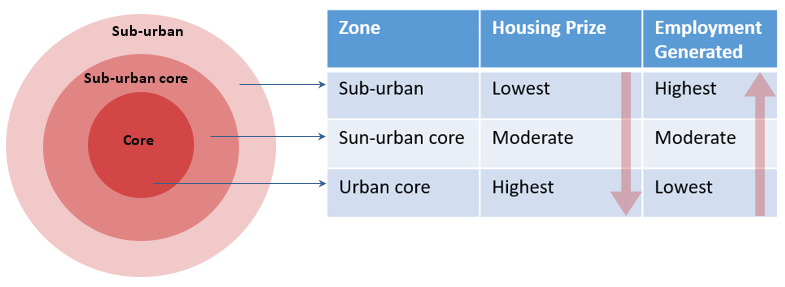

The built environment can be dissected into three major aspects of variables as mentioned below:

- Density: which can be calculated based on the population, dwelling units, employment generation or built-up area found in the area of study.

- Diversity: which can be determined by calculating either the land use mix index or entropy index or the dissimilarity index of the studied area.

- Design: this variable can be scrutinised based on the dimensions and proportional aspect of the built form of the area of study.

The Elasticities of the Built form Variables

Prof. Robert Cervero’s paper, Travel and the Built environment, 2010, where transportation data of 50 different cities of the USA was collected and studied to understand the relation between the 3Ds and the VMT (vehicle miles travelled), usage of transit and walkability aspect of the built environment. He eventually came up with elasticities, i.e., how percentage of one quantity result in percentage change in other due to their interdependency, which are explained below:

- Elasticity of VMT: increase in values of the ‘3Ds’ result in decrease in VMT. L-U mix and street density play significant negative impact here.

- Elasticity of transit use: Increase in values of the ‘3 Ds’ result in increase in transit use. L-U mix and design play significant positive impact here.

- Elasticity of walking: Increase in values of the ‘3 Ds’ result in increase in walkability. L-U mix, job-housing balance, distance to store and street density have a significant positive impact on walkability.

Read more: Climate change mitigation in the Transportation sector through Urban planning

Urban Development and Mode Choices

There are various aspects that work together to finally determine how people choose their modes of travelling in and around a city.

Urban Aspects that affect Mode Choices

The socio-economic and cultural tangent is one such aspect, while the build environment/ urban development of the city is another. These two aspects are very specific characteristics, unique to a city or region, and have direct implications of travelling systems of a city.

Urban development here works by interconnections of compactness, mixture of L-U and walk-friendly environment near the origin and destination points.

Cost, socio-economic and cultural aspect work by interconnections of time, distance and attributes of the mode of travel.

These two broad aspects working simultaneously, finally contribute towards the decision of mode choice of the user.

Binomial, Multinomial Logit Model & the Utility Function

Logit models are a statistical tool to determine the probability of a transit mode to get used by the users in a city. There are two types of such models used in transportation planning.

The components of utility expressions in most multinomial logit formulations of mode choice weigh generalized costs of getting between points A and B as well as trip-maker characteristics, but they don’t account for the influences of points A (origins) and points B (destinations) in explaining mode choice As a result, the potential effects of density, land use combinations, and urban architecture in and around travel origins and destinations are often overlooked.

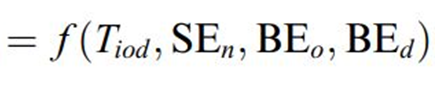

Therefore, the utility function must account for the characteristics of O & D. For this Robert Cervero proposed an expression of the utility function to better predict the mode choices. He took a normative approach towards predicting influences of the built environment on mode choices.

From the equation, it can be inferred that the probability is expressed as a function of not only the socio-economic aspect but also the built environment.

- Pniod is the possibility that person n will travel between origin o and destination d using mode i.

- Tiod is a trip interchange vector that includes travel time and cost for journeys by mode I from o to d.

- For trip-maker n, SEn is the socio-economic vector, which includes factors like income and car availability.

- BEo is the built environment vector at o, which includes indicators such as land use intensity, land use mixing, land use accessibility, and walking quality.

- The built environment vector for d is BEd.

Inferences

- High density and L-U mixtures work in favor of public transportation & against drive alone & group ride automobile travelling.

- The probability impact of L-U on mode choices is transferred to other binomial variables, thus the multinomial logit model is more appropriate and accurate.

- Out of the built env. variables, the L-U diversity in origin and destination has maximum impact on mode choice.

Key Takeaways

- Transportation planning and policy making should aim at moving people rather than moving vehicles.

- Incorporating Transportation Planning at Urban Planning stage is important.

- Developing reliable public transportation system, walking and cycling infrastructure with safety is important.

- Last mile connectivity is important.

Applications & Case Studies in Urban Planning

There are numerous applications of integrated land use, comprising of built environment (density, diversity and design) and transportation planning, comprising of travelling and mode choices (VMT, NMT and transit) as stated below:

- : Focuses on dense, compact urban form by magnifying residential, commercial, and recreational space within walking distance of public transportation.

- Smart growth in urban planning: Small, walkable, bicycle-friendly land use and mixed-use development emphasizes expansion in compact, walkable urban areas to minimize sprawl.

- Transit village: Around passenger rail terminals, communities with a bus, railway, or ferry station can encourage economic growth, urban renewal, and private sector investment.

- New urbanism: Town with closely packed housing, jobs, and commercial areas to decrease reliance on cars and to promote liveable and walkable neighbourhoods.

- Infill housing: Building single-family houses in existing neighborhoods with new commercial, office, or mixed-use buildings.

- Cluster development: Attempts to strike a balance between expansion and open space preservation in rural and suburban areas.

Read more: Impact of Urbanization on landuse change in the rural-urban fringe (Rurban)

Transit-oriented development: Ahmedabad

Ahmedabad demonstrates a step-by-step adoption of TOD. In response to declining public transportation utilization, Ahmedabad built the “Janmarg” Bus Rapid Transit System. Due to the Janmarg’s operational success, policy directions utilizing the BRT to accomplish TOD have been implemented.

The Janmarg Story – Laying the groundwork for TOD

The idea was to limit stretch by fostering a compact city form with higher densities in regions where public transit was available. The city’s development plan for the city’s central business district stresses mixed-use, high-density construction, public transportation, a pedestrian circulation network based on a grid, and a market-driven approach to land use.

Ahmedabad’s central city area is characterized by business, mixed-use, and significant residential neighbourhoods on the outskirts. Several industrial-zoned parcels of land are located close to housing neighbourhoods inside the administrative limits of the city.

Traditional TOD rules are followed by the recommended recommendations. Furthermore, the municipal corporation’s housing strategy emphasises the integration of transportation and commercial activities along the BRTS lines.

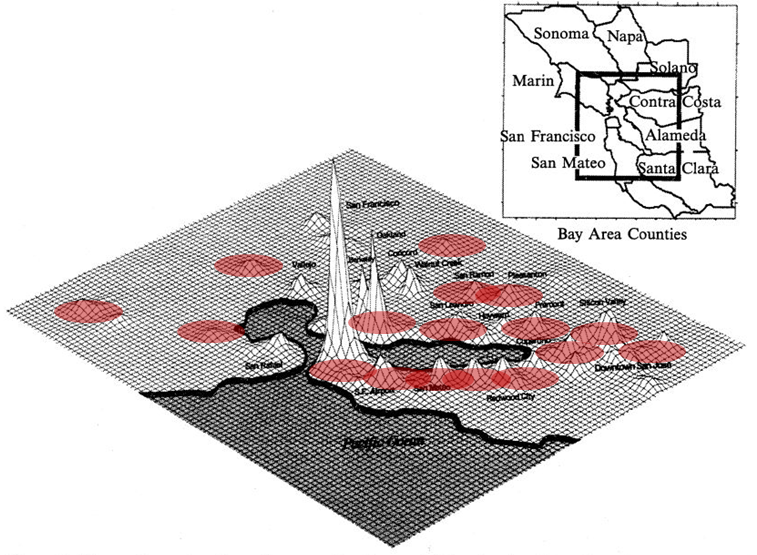

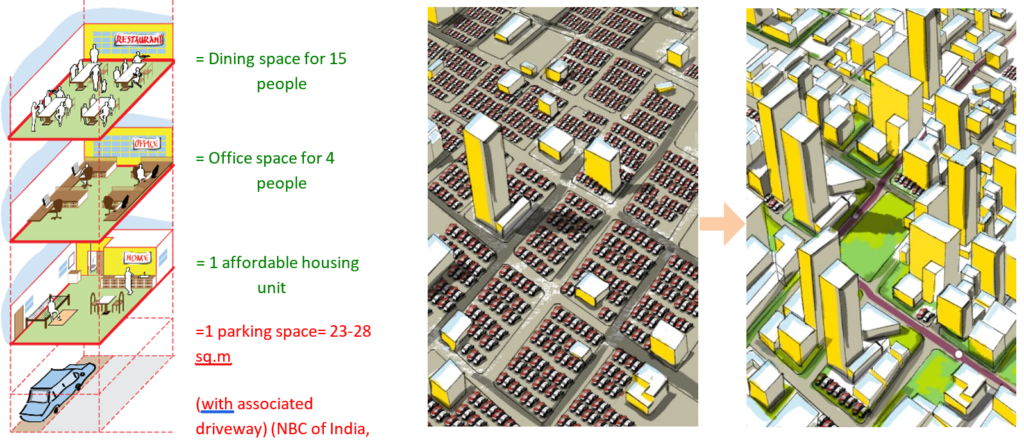

Infill Housing: Polycentric Bay of San Francisco

The bay of San Francisco has developed as a polycentric settlement over the years because of its topographic conditions. The typical characteristic of each such centre has characteristics as shown below:

(Source: R Cervero, Polycentrism, commuting & residential location in San Francisco Bay 1997)

As a result, the ULBs had to invest millions of dollars in Transportation Planning and in transit & roads. A better solution would have been to implement a non-selective L-U policy.

Fusing multilevel residential towers with apartments, affordable by an average employee, instead of just maintain the existing sparse development. Applying appropriate L-U planning is an integral part of transportation planning and can save resources, time & money

Transit Village: Richmond Village

Contra Costa County’s Richmond Transit Village is a 17-acre mixed-use development, transit-oriented infill project. The project, which will be located between the Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) and Amtrak stations in Richmond, will provide high-density housing within walking distance of public transportation. The main goal of the project is to work ahead of time with the city, local businesses and people, developers, transit agencies, and government partners to plan for the station’s and the station area’s continued economic development, particularly along Macdonald Avenue.

(Source: National planning excellence awards: implementation, 2012)

Project Implementation

The transit village project was made possible by BART and the Richmond Redevelopment Agency’s creative decision to repurpose the existing station site for future residential construction rather than surface parking.

Outcomes

To present, roughly 800-900 housing units have been allowed in the downtown area, the majority of which are on the undeveloped ground.

The design is expected to provide 1,240 extra transit trips per day and improve pedestrian and bicycle activity, however, increased traffic congestion at some junctions may necessitate mitigation.

The traffic impact study for the plan was done using the LOS (level of service) technique, with an emphasis on automotive traffic and vehicle delay, as well as the influence of the plan’s transit investments and bike/pedestrian features on decreasing motor trips.

Policies/Ordinances that Aided in the Success of the Project

The village has effectively repurposed underused property while also encouraging transit use and house ownership. Despite an increase in overall affordable housing production, Richmond wants to see more affordable apartments.

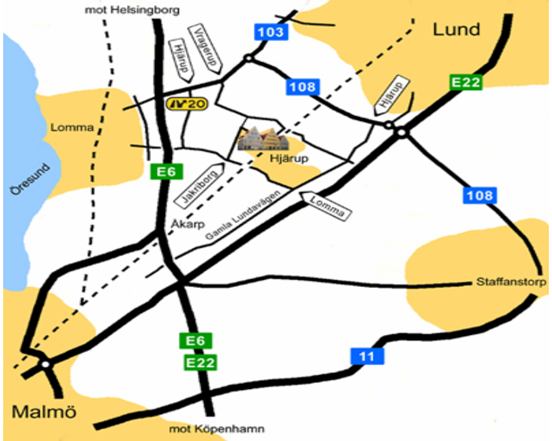

Neo-traditional Town Planning: Jakriborg

With its historical architectural style, notably the mediaeval style, Jakriborg is an expression of the ideas of Traditional Neighbourhood Development. This is a one-of-a-kind example of a new town designed purely for pedestrians, with parking for automobiles restricted to the town’s boundary. The layout includes a central pedestrian roadway, market square, and common green, which together form the town’s denser core. These exhibit strong interest in aesthetics and come close to meeting diversity.

(Source: Blekinge Tekniska Högskola International Master’s Programme in European Spatial Planning 2004/2005)

It also adheres to the new urbanist notion that more distinctive design facilitates a stronger feeling of place and communal identity.

The effective integration of commercial areas in the development is notable. Local businesses as well as a grocery chain have set up shop on the first floors of two adjacent buildings.

In most aspects, the community has been successful from the perspective of New Urbanism. Jakriborg is also served by a commuter train line that runs between Malmö and Lund. More pedestrian and car links between the two sides are planned as Jakriborg grows, as its owners want.

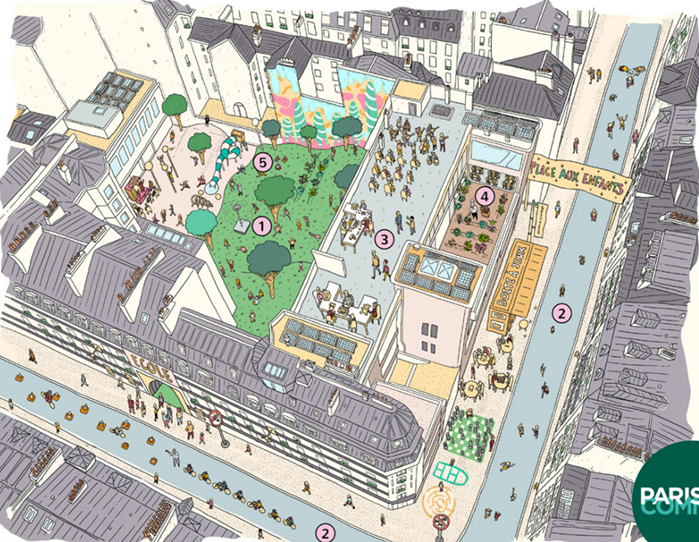

Hyperlocal development: Paris’s Street Re-design

The hope here is to reimagine cities not as distinct zones for living, working, or leisure, but as ‘mosaics of neighbourhoods’ where these uses can coexist in the most accessible and diverse way.

(Source: complete streets in the 15 minute city, 2021)

An example of Paris’ Street redesign for the hyper-local vision.

- A crossroads has been renovated into a community square.

- A place for the community to come together.

- Children’s games

- A garden that may be shared.

- Renewable energy and freshness

(Source: complete streets in the 15 minute city, 2021)

An example of Paris’ Street redesign for the hyper local vision:

1. A courtyard that has been turned into a weekend garden.

2. A pedestrianized street for children, at least during pick-up and drop-off times.

3. New opportunities for youngsters to learn about culture, the environment, crafts, and other topics.

4. Organic foods farmed locally and supplied to kids in cafeterias.

The Problem of Parking

When it comes to ILUTP, the issue of private motorisation becomes imperative and so does the problems associated with it, one them being parking.

Parking: a commodity or a right?

In India parking is seen as a right rather than an economic commodity. Management of road encroachment by illegal parking is poor and done well in only few parts of the city.

The by-laws drive projects to provide a minimum number of parking spaces. This in turn generates the need or scope of cars to fit in the limited area of the city. This cycle continues and the requirement for parking becomes vicious and endless. Instead, a more humane way of using roads must be applied with importance to activities like recreation and social spaces.

Therefore, instead of creating more and more Multi-Level Car Parking, Low Income Housing, Public open spaces or Social Amenities should be provided. Instead of by-laws stating to provide ‘minimum parking’, ‘maximum parking’ requirements should be recommended. By minimising parking, there is a greater opportunity of creating a people-oriented city with integrated humane aspects.

Case studies: Parking as Commodity

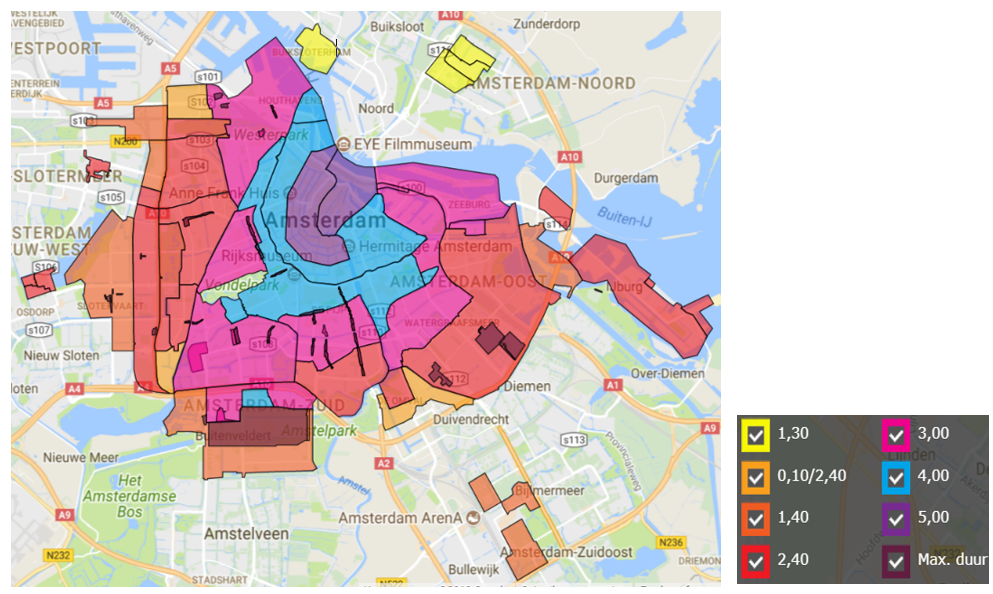

There are 7 parking zones and per hour parking rate and timings varies as per each zone for visitor parking.

(Amsterdam Parking Plan, 2012)

Parking price ranges from €1.3/hour to €5.00/hour. The prices in city centre are kept very high, so as to avoid unnecessary parking on the streets. Parking may or may not be free on Sundays and public holidays depending on zones. This showcases a good example where parking is seen as an economic commodity.

Policymaking Towards Green Mobility in India

Major issues to be handled in transportation planning in India are (1) Air quality indices and

(2) Congestion on roads

National Urban Transportation Policy, 2014

The basic aims of the NUTP are to use road space to move people rather than automobiles, to include urban transportation into urban planning, to encourage seamless, user-friendly, and dependable public transportation, and to promote walking and cycling as safe modes of urban transportation. Read more about the policy here.

National Transit Oriented Development Policy, 2017

Despite the fact that 17 smart cities have adopted components like as first- and last-mile connectivity and multimodal integration, several have yet to make significant progress in creating NMT networks. To make the policy more adaptable throughout India, adjustments to the DCRs, as well as the overall design and architectural level, must be made to account for floor area ratio suggestions in varied locations.

Smart City Mission

According to a survey, the most important NMT activities in the Smart Cities project in 20 cities were public bicycle sharing programs, electric bus and electric rickshaw fleets, IT-enabled fleet tracking for e-mobility options, and EV charging and parking places.

National Mobility Mission Plan

The NEMMP report offers detailed predictions and situational analysis, predicting India’s potential to become a global EV market leader by 2020; nevertheless, the estimates have fallen short, and India is not even among the top 20 nations in terms of EV usage or manufacture.

Conclusion

Using Integrated Land use and Transportation Planning as a strategy of urbanisation can result in worldwide sustainability by achieving a few SDGs as mentioned below.

Thus, by using appropriate applications, policies, planning implementations and design of ILUTP, we can achieve sustainable urbanisation and a better future.